Several parents have asked me over the years, “What did you do to fuel your son’s passion for science?”

As someone who became a math major in college with the hope of someday realizing my dream of working for NASA and the space program, I used to love watching my son develop an appetite for science. It was deeply satisfying for me to see him explore his personal interests in geology and paleontology – interests that would not only eventually become hobbies and science fair projects, but would also lead him to a career in these and other science-related areas when he grew up. Don’t we all yearn to have fun at our jobs?

A lot of his interest in science was originally sparked by taking him to the Museum of Science and to the Aquarium, where he was first introduced to the “ooo’s” and “aaaahhh’s” of biology, chemistry, astronomy, oceanography, electricity and… dinosaurs. What kid (or adult) isn’t fascinated with the Van de Graaff generator, the huge T-Rex, or real sharks in huge tanks?

It has been well documented that many students lose more than 2 months of knowledge over the summer. The courses my son took at the science museum and aquarium, on weekends and especially during summer when he was in elementary & middle school student, allowed him to have a hands-on experience in “the art of experimentation” with activities, materials and equipment that I couldn’t afford to supply at home, at an age when it could (and obviously did) make a lasting impression.

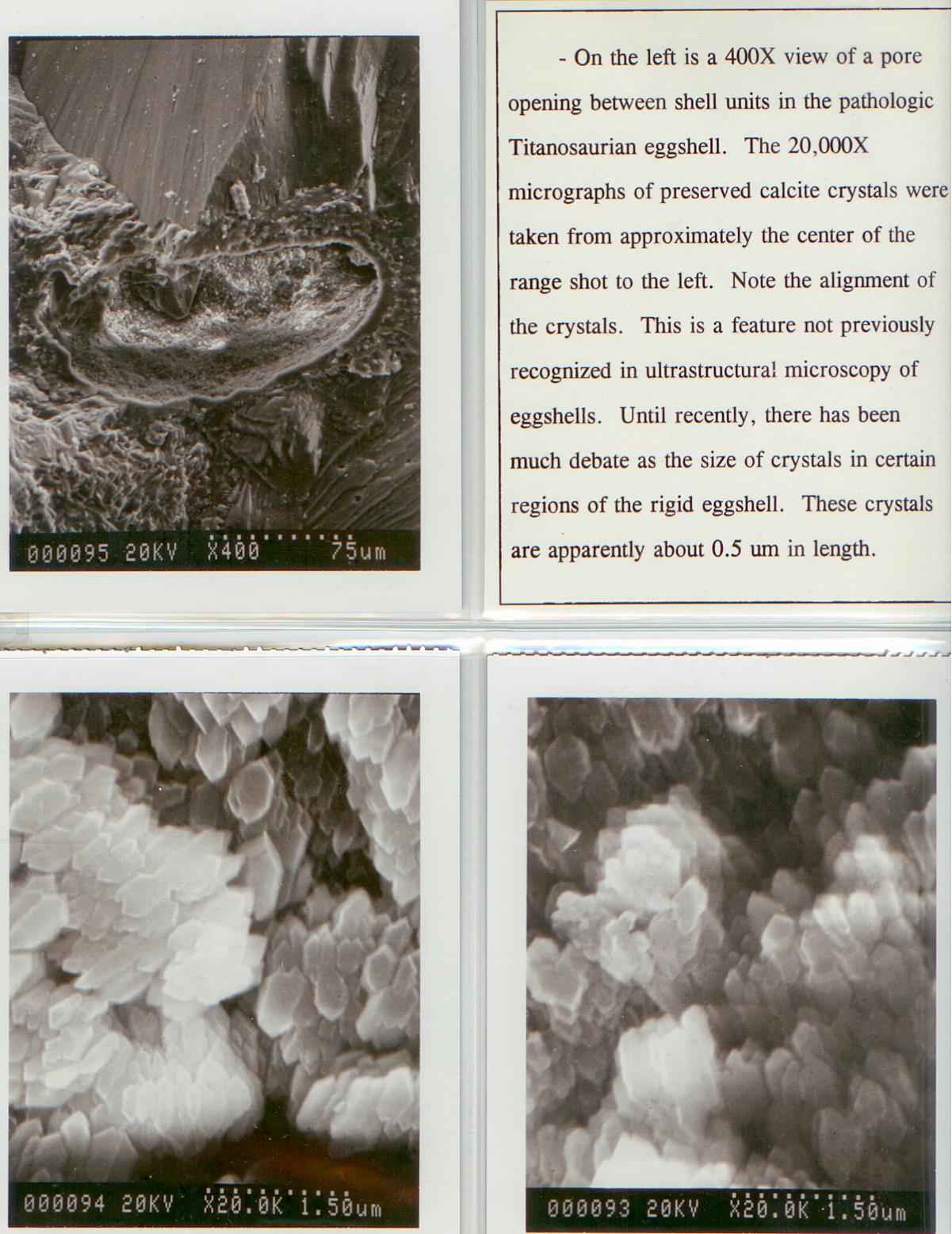

When it came time for him to start working on school science projects and his science fair projects, the contacts he had made at the Boston Museum of Science, in particular, were invaluable to opening many doors. The Museum staff not only helped him develop his project ideas, but helped him to find access to materials, labs and equipment not often available to someone so young.

The most valuable thing you can do to help your child start developing an interest in the fascinating world of science this summer is to encourage regular visits to a science museum, aquarium, zoo — or even your local library or bookstore where they host workshops, so your child can be introduced to the Science, Technology, Engineering & Math (STEM) subjects that most interest him or her.

When your child expresses an interest in a specific topic, nurture their natural curiosity until it blossoms into their own experiment or project. A museum course instructor or workshop leader may even agree to become a mentor to your child, and may be best equipped to help your child to expand upon ideas and interests.

Have a great summer!

![Flask_girl-[Converted]](http://mistersciencefair.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Flask_girl-Converted-207x300.jpg)