I remember reading an article several years ago in Time magazine (Monday, Apr. 10, 2000) about a debate between Paul Hoffman, former editor of Discover magazine & past president of the Encyclopedia Britannica and John Horgan, author of a controversial book, The End of Science.

In the debate, Horgan tried to convince Hoffman that “…we’ve discovered all we can realistically expect to discover and that anything we come up with in the future will be pretty much small-bore stuff.” If you buy this line of thinking, then there is no reason to have any more science fairs!

Astrophysicist John Bahcall, who helped to prove what makes the sun shine, said it best, “The most important discoveries will provide answers to questions that we do not yet know how to ask and will concern objects we have not yet imagined.”

Let’s look at the evidence of some of the biggest scientific breakthroughs and discoveries over the past 16 years…since the Discover article was released:

- The human genome project was completed

- Two teams of scientists, one in Wisconsin the other in Japan, announced their discovery of a way to make stem cells without using embryonic stem cells.

- The evidence of gravitational waves was discovered.

- The first self-replicating, synthetic bacterial cell was created.

- An artificial liver was developed to be used as a bridge for the liver transplant, minimizing the chances of liver failure.

- The discovery of a previously unknown human ancestor, homo nalendi, was found in a cave in South Africa.

- The development of the first new antibiotic in 30 years – teixobactin – to fight growing drug-resistance.

- The World Wildlife Foundation announced the discovery of 211 new species in the Eastern Himalayan region, including 133 plants, 39 invertebrates, 26 fish, 10 amphibians, one reptile, one bird, and one mammal.

- The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) was built, a 17-mile-long looped track located an average of 300 feet beneath the Earth’s surface under the Swiss-French border, which accelerates two beams of particles to 1.2 trillion electron volts (TeV) and then smashes them together. The solving of the Higgs boson is said to be one of the greatest scientific mysteries of modern times.

- Scientists at the Genome Sequencing Center report that they have sequenced all the DNA from the cancer cells of a woman who died of leukemia and compared it to her healthy cells. In doing so, the experts found mutations in the cancer cells that may have either caused the cancer or helped it progress. It is the first time scientists have completed such research.

- Water was discovered on the surface of Mars

- Scientists have created a vaccine that seems to reduce the risk of contracting the AIDS virus.

- Scientists have published the first comprehensive analysis of the genetic code of the Y chromosome.

- The Hubble telescope has detected the oldest known planet—and it appears to have been formed billions of years earlier than astronomers thought possible, 12.7 billion years ago.

- Two new solar systems were discovered.

- The world’s first vaccine was developed against the malaria parasite, which has been shown to be effective against even the most deadliest strains.

- Jadarite was discovered; it is an essential component in the production of batteries for cellphones, computers, and electric or hybrid cars.

- Exoplanets have been confirmed to exist revolving around distant stars similar to our sun. As a result, we may begin a rethinking of the universe and our place within it.

- A vaccine preventing cervical cancer was developed.

- Then, there were the inventions of the iPod, the iPhone, hybrid cars, the Segway transporter, 3-D printing, augmented reality, and using water as fuel.

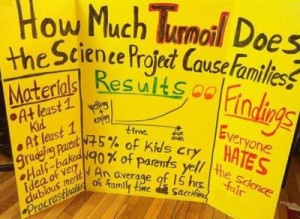

While there may be a debate about which of these or other discoveries are the Top 10 of the past fifteen years or so, there should be no question that the above evidence illustrates how important it is to train and support the next generation of scientists.