A man, in Chechnya, next to the so-called “largest dinosaur eggs in the world”

A few months back there was a report that the world’s largest dinosaur eggs had been discovered in Chechnya (do a google search for “world’s largest dinosaur eggs” or something like that and you’ll see links everywhere). It made it to worldwide news within days, and was even reported on ABC News. Chechen officials were ecstatic that there may be a surge in tourism and revenue to their local economy. In fact a number of dinosaur enthusiasts, mostly local, did try to visit the site in coming days and weeks.

Around the same time a report came out from the University of Zurich (Dr. Marcus Clauss, and others) that one of the major reasons for large dinosaur extinction was the fact that dinosaurs had to lay eggs. Although dinosaurs kept getting bigger (for instance the Titanosaurs which are well known from fossils in Argentina, and thought to be some of the largest animals that ever lived — there were several dozen species, some of which could have weighed up to 100 tons), their eggs were getting comparatively smaller. An average Titanosaur’s eggs were only about a foot in diameter. So, the babies inside would have only weighed a few kilograms — a far cry from the at least 50 tons they were expected to grow to, as an adult. Eggs are designed this way in part because there are physical limitations to airflow through a membrane, which means that in order for the egg to retain its strength it had to remain small enough for oxygen to get inside, and carbon dioxide to get out. It is theorized that because the babies of the large dinosaurs had to occupy such a widespread niche in the dinosaur’s ecosystem, there were comparatively fewer small dinosaur species around, which could have survived a massive extinction event. Furthermore, as babies the dinosaurs would have largely fended for themselves, whereas mammals, and smaller birdlike dinosaurs were more involved in the raising of their young. This meant the large dinosaurs were more likely to die off in a catastrophe with a food shortage.

The largest dinosaur eggs ever discovered were found in China in the 1990′s, and were 2 feet (60cm) long, and around 20 cm in diameter. Much smaller than 63cm to 1 m, which was the originally reported size of the “eggs” found in Chechnya. Considering that the largest vertebrates which ever existed had eggs about a third of this size, you’d have to wonder how big the animal was, that laid these huge eggs.

Having studied dinosaur eggshells for a number of years, when you hear something completely astonishing like this, you have to regard it with a careful scientific eye, if not outright skepticism. The claim that the eggs had widely varying diameters, and the “yolks” and “whites” clearly visible were a key indicator that the eggs may not be real. Dinosaur eggs are rarely discovered intact, and moreover, they rarely have consistent, clearly divided sections, and are without lots of eggshell evidence around. As a young budding paleontologist, in my middle school years, I had the opportunity to study at “Egg Mountain” – the first dinosaur egg nesting site in North America made famous by Montana’s Dr. Jack Horner. I recall that for every partial egg you found, you’d see tons of eggshells along the way leading up to it, which were so plentiful, and so scattered, you wouldn’t even bother to collect them. Like modern chicken eggs, dinosaur eggs would have been relatively speaking, fragile, and could shatter, and as dry eggshells, spread easily all over the ground.

Barnas Monteith, with Dr. Jack Horner, at a site near “Egg Mountain”, the first dinosaur nesting site discovered in N. America

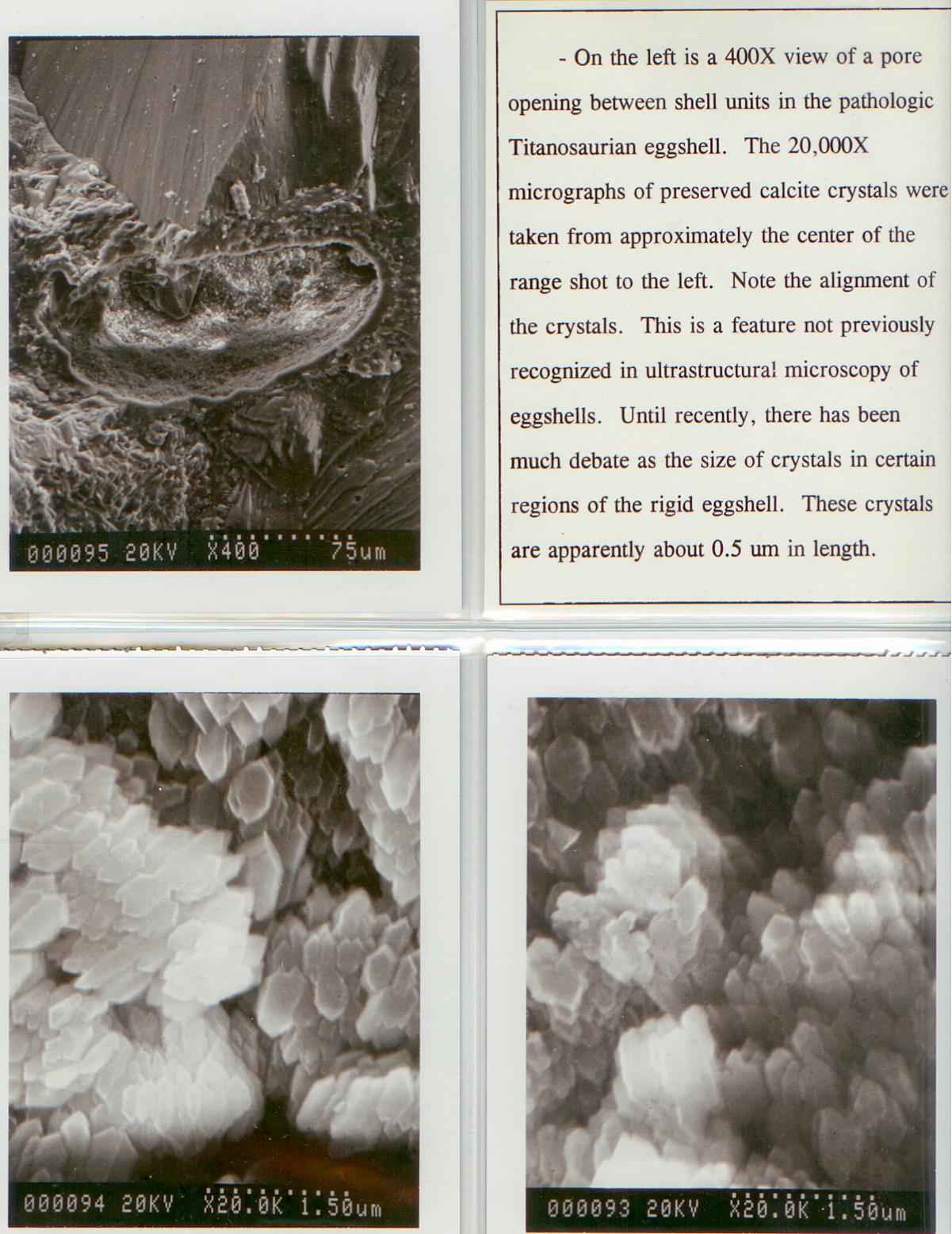

Part of the reason that eggs and eggshells are so complicated is because they have to serve a bunch of different purposes. They have to 1) protect the embryo from the environment and predators somewhat, like armor, 2) protect the embryo from toxins, 3) allow the baby to breath, 4) be able to be broken by the baby when it’s time to hatch. There are a number of other purposes too, but these are really the main ones. Eggshells are made up of a mixture of both organic (protein-based) materials and inorganic (calcium carbonate usually, and sometimes calcium phosphate, like bones) materials. The eggs contain an inner lining of a membrane which helps keep bacteria and other toxins away from the whites and yolk, and pores which allow for gas exchange. It is this membrane that serves as a growing point for the fibers and calcium carbonate crystals which act as the “skeleton of the egg”. Below is a picture of a modern eggshell which I took with an SEM for comparative purposes, when I worked at Harvard’s OEB lab, trying to determine if an egg-like fossil from the Triassic was really a membrane based egg. Now that was a tough project, and still has no firm conclusion.

A scanning electron micrograph of a membrane-based eggshell, at very high magnification, in which you can see the proteinaceous fibers embedded in the inorganic calcium carbonate matrix

So, when you look at the initial pictures of the eggs from Chechnya, you see something quite interesting. You see concentric circles around some of the eggs, which is pretty inconsistent with the growth patterns of normal eggs, which grow from the membrane out, and not as large, single spherical shells from one end to the other.

Chechnya’s “dinosaur eggs” containing circular patterns around the eggs, indicating that it is a likely concretion rather than an egg

They look a lot more like the concretions or “bowling balls” like the ones here on bowling ball beach in California (a real place).

Mendocino, California’s Coastline “bowling ball beach”

From philwendt.com, a picture of concretions from CA – note that the rock in the left center appears to look a bit like a cut hard boiled egg, due to various mineral stains., but alas, it’s just a rock – not a fossil egg.

It wasn’t even days after the ABC report came out that scientists came forward with publicly expressed doubts. A month later, a Russian university report came out which finally declared that the “eggs” were nothing more than rocks. In more recent months, people with access to the specimens have confirmed that these “eggs” were indeed nothing more than concretions and should have been checked more thoroughly before an announcement was made.

Even more recently articles have been published that a set of small meat-eating (Theropods, like Velociraptor) dinosaur eggs was found that resemble the morphology (shape) of modern bird eggs, in that they are oval and elongated. This suggests that just maybe, the small meat eating dinosaurs may just have evolved into birds in the nick of time, and became the very birds we see today. A paleontologist Nievez Martinez, who passed away over a year ago, discovered this group of ovoid eggs, and was able to do research on this amazing discovery before her untimely passing away. More on her research can be found here: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/07/120712092443.htm.

In fact, there are more recent scientific studies as of this week (http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/10/121011141443.htm) that add further evidence to suggest Steven Jay Gould may just have been right that vertebrate evolution occurs in short, necessary bursts, based on a basic genetic developmental toolkit which has existed for hundreds of millions of years (published a few days ago in Science). The differences between a very light hollow-boned hunting dinosaur with feathers and a very light hollow-boned bird with feathers and wings is really very very small, given the huge variety in species today. It’s still possible that some of the birds you see flying around today, are distant cousins of T-rex, or at least maybe Deinonychus or Velociraptor. One can only wonder and hope.

This is yet another Furious Case of a Fraudulent Fossil… I am not sure that this one was solved by the Galactic Academy of Science though. But you never know…

If you’d like to read more about how the Galactic Academy of Science solves cases of Fraudulent Fossils, please buy my new book here (and this book has a LOT to do with dinosaurs to bird evolution, and fossilized eggs). Note that the link below is a sneak preview of what the second edition cover of “Fraudulent Fossil” will look like. But, for now the first edition is a collector’s edition, so buy soon:

Click here to Read More and Buy “Fraudulent Fossil”