Informal science education, such as the type of learning a student gets outside of the normal classroom environment by participating in a science fair, provides kids with an in-depth and hands-on look at “real world” science. While it’s possible that participation in a science fair can open doors for students who have already discovered their abilities and passion for science, it can also help students develop an interest in science which could be important to them no matter which career they choose.

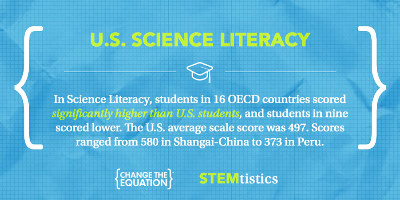

Some of the most important arguments for the Next Generation Science Standards are: 1) American students are falling behind in math and science, performing at levels below students in competitor nations on international tests. In the most recent results, the United States slipped from 25th to 31st in math since 2009; and from 20th to 24th in science; 2) fewer students are pursuing careers in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) disciplines, and 3) science is profoundly important to address the problems we’re now facing such as preventing and curing diseases, maintaining supplies of clean water and addressing the energy crisis.

Source: Programme for International Student Assessment, OECD, 2012.

Our collective futures are dependent upon students being interested in science. The purpose of more science education, broadly expressed as ‘STEM literacy’ is to motivate all students (not just the parents and students who are already a fan of science) to fully engage in the very active practices of science and engineering. Aside from the movement to provide 100,000 STEM teachers over the next decade, the other important reason to help your child become interested in science is that through the Next Generation Science Standards, students will be tested on STEM literacy in school.

As your child passes through all grade levels, the new Next Generation Science Standards testing will be evaluating your child’s skills and capabilities in areas such as:

1. Asking questions (for science) and defining problems (for engineering)

2. Developing and using models

3. Planning and carrying out investigations

4. Analyzing and interpreting data

5. Using mathematics and computational thinking

6. Constructing explanations (for science) and designing solutions (for engineering)

7. Engaging in argument from evidence

8. Obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information

In essence, the new standards recognize that “science, engineering and technology permeate every aspect of modern life” and that by the time a student graduates high school they “should have sufficient knowledge of science and engineering to engage in public discussions on science-related issues, to be critical consumers of scientific information related to their everyday lives, and to be able to continue to learn about science throughout their lives.”

Scientists are no longer just a bunch of old men in white coats with goggles, pens in pocket protectors, grumpy attitudes and an inability to talk about anything other than research. Elon Musk, at 36 was named Entrepreneur of the Year. Why? Because by then he was already the CEO of Telsa Motors and Solar City, was co-founder of Paypal and was the then head-rocket-designer for SpaceX. 38-year-old Mayim Bialik who plays a neuroscientist on The Big Bang Theory has a PhD in Neuroscience in real life!

A non-scientist – but someone who has an interest in, and an understanding of science – might be the salesperson at the appliance store who can help you select the most cost-effective furnace, or the grocery store clerk who understands the potential for botulism if meat isn’t properly refrigerated, or the politician who’s fighting for a clean-energy policy.

Science is all around us, and it benefits everyone at every age, to become more science literate.

![Flask_girl-[Converted]](http://mistersciencefair.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Flask_girl-Converted-207x300.jpg)